2.10.2018

Will algorithms take over chartering?

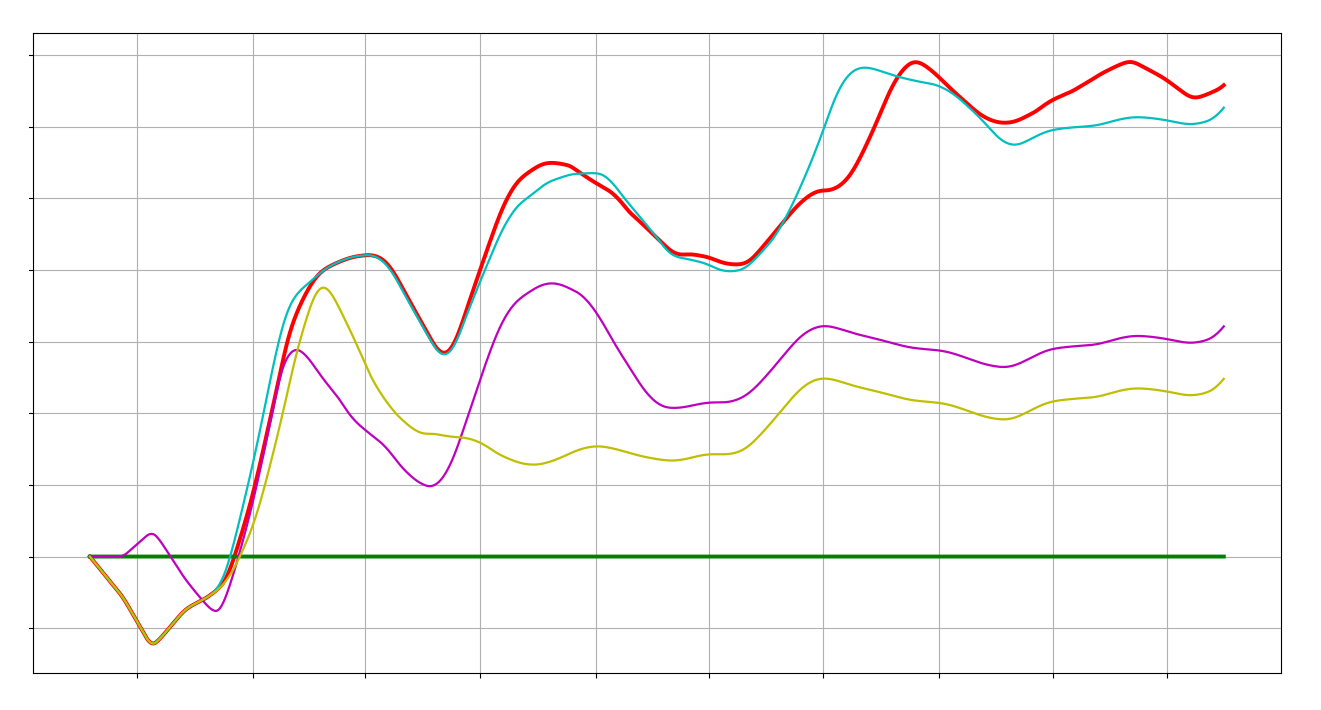

The latest big idea in the startup world is to improve the commercial management of a fleet by using "big data" and advanced optimization algorithms. The objective is to dynamically optimize the positioning of the fleet - that is - choose the right sequence of trips given forecasts of rates across the different routes. The Maersk Tankers/Cargometrics tie-up is well known, companies like Fractal Logistics and Signal Ocean are already basing commercial management on algorithms, and a handful of others are still trying to work in stealth mode with varying degrees of maturity.The question which ought to be on every potential investor and industry partner's mind is: What is the upside? It's a tough question to answer, but not impossible. In his recent PhD work, our own Vit Prochazka took a good stab at it for the drybulk market.As usual, we have to make some reasonable assumptions to make it work: every vessel is 'Baltic type' and obtaining the Baltic tripcharter rates (no cheating with better specs); you can only trade the standard Baltic fronthaul, trans-Atlantic, trans-Pacific and backhaul trips; you are always fixed immediately upon finishing the previous trip (no waiting between contracts); and the trip duration is random within the ranges set by the Baltic (e.g. 30 - 45 days for TA).Without going into the technical details (save to say that it involves dynamic programming and neural networks depending on the nature of the problem), we are in the end able to compare the performance of different type of operators: the guy who flips a "coin", the "oracle" who has perfect foresight for the entire horizon, and the players who can also see future freight rates but only with a limited foresight (LF) horizon of 20, 50 and 80 days, respectively. The former category is approximately equivalent to just making the Baltic TC average index and is our benchmark. The "oracle" obviously represents the upper bound to outperformance, and the guys with limited foresight will end up somewhere in the middle. Realistically, a good forecasting model for the individual routes may be able to get sufficiently good results a few weeks ahead.The two graphs below shows the resulting outperformance (cumulative earnings in excess of the benchmark) for a Capesize and Panamax vessel managed in accordance with the out-of-sample trading signals from the optimization algorithms for the period Oct 2013 through Dec 2016.

There are a couple of key takeaways here: Capes do better than the smaller vessels (we have also looked at Supramaxes), with an "oracle" trader making an average of $3200/day in excess of the index, compared to around $1100/day for a Panamax. This is because of the generally greater volatility of Cape rates (and their regional differentials). These daily numbers sound good, but are not achievable in practice. In a best case (i.e. having decent forecasts for the next 50 days) you can capture about 50% of that upside. Still not bad.More worryingly, though: The bulk of this outperformance comes in the first part of 2014 when the drybulk market had not yet flatlined. Once the market depression hits in 2015 and 2016, even knowing future freight rates with certainty up to 50 days ahead does not help you to beat the index. That also makes sense: During this period there was a substantial oversupply of vessels that could quickly take advantage of any regional opportunities, and as a result the upside never really materialized.So there you have it: The short term payoff from investing in analytics and algorithmic chartering is market dependent, and current volatility, at least for Capes, means it is probably not such a bad time to go for it. However, keep your expectations properly calibrated.Of course, in the long run, smarter chartering and greater efficiency will likely remove even these last remaining opportunities. That is easy to forget in the excitement.All told, algorithms will not take over chartering because they do a much better job than the current highly efficient network of humans but because they are cheaper to run.(We acknowledge that there may be more profitable opportunities at a higher spatial resolution, i.e. local short-term squeezes on tonnage, which could increase these estimates. Also, some additional gains can likely be had from speed optimization, opportunistic waiting etc.)